As Mary Daly and other feminists have noted, holding the Virgin Mary up as the model for motherhood is an unobtainable and unfair standard for women. That being said, the history of Mary’s motherhood in art and doctrine is particularly interesting.

The parallel between Eve and Mary dates from the very beginning of Christianity and resonates throughout the writings of the patristic fathers. Hence, in Christian consciousness, Mary is not only “Mother Nature,” but the mother of humanity.

In Paul’s Letter to the Romans he mentioned that Jesus’ redemption saved the world from sin and death that Adam’s acceptance of the forbidden fruit brought into the world.

In the second century, Ireneaus was credited for his theory of recapitulation that established Jesus as the New Adam and Mary as the New Eve. But virtually all of the patristic fathers who wrote anything about Mary compared and contrasted her to Eve. This comparison shaped the Church’s teachings about Mary and its attitude about women’s social and religious roles.

The concept of Christ as the New Adam as was articulated by the early church fathers- especially by Ireneaus in the second century with his theory of recapitulation. (New head of humanity).

At the same time, Mary was consistently hailed as the New Eve and her perpetual virginity proclaimed at 2nd Council in Constantinople in 381 (under Constantine). The two worked together in the minds of the early church fathers. Much is written about her virgin motherhood and the life she brought to the world (through Jesus) in contrast to the death (and sex) introduced to the world by Eve.

Consequently, in Marian art, we find a lot of the symbolism from the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden from (Genesis 3):

fruit (apple)

gardens

trees:

Looking at the painting in the heading, The Virgin Under the Apple Tree by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530, note the lush garden setting and how the rosy-golden apples in the tree are almost arranged in a halo around Mary’s head—to signify her “fruitfulness” despite her virginity. In this painting Jesus looks right at us, wise beyond his infancy. He holds an apple in one had and a torn piece of bread in the other – this symbolically contrasts her physical fruitfulness and sustenance with his spiritual fruitfulness and sustenance—which precludes his later role as the “bread of life.”

Other consistent “New Eve” themes in Marian art are:

clothing vs. nakedness, etc.

the serpent

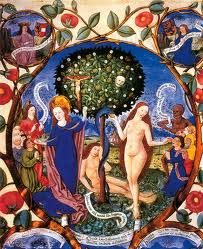

Some Marian art specifically places her in comparison/contrast to Eve: Take, for example, the book illustration by B. Furthermeyr, Mary as the New Eve under the Tree of the Fall, 1481. Bavarian State Library, Munich.

Note the abundance of life on Mary’s side and death on Eve’s. Adam is positively drunk with sin, and is very well grounded under tree (remember his punishment was to toil tending the earth) The serpent is spiraling up the trunk of the tree, literally, from Adam’s male person. Mary is modestly and heavily dressed in contrast to Eve’s stark nakedness.

The key concept upon which Mary was established as the New Eve is based on the story in Luke’s Gospel when the angel Gabriel visited her and told her she was to bear the Son of God. It is in this narrative story, referred to as the “Annunciation” when Mary proclaims her famous “Magnificat” saying, “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord, May it be done to me according to your word.”

In the minds of the Church fathers, Mary’s “obedience” allows redemption from the sin to be brought to humankind that was originally introduced to the world through Eve’s “disobedience” in choosing to pluck the fruit from the tree of life. And the actual words they use repeatedly in making the distinction between Mary and Eve are “obedience vs. disobedience.”

As a result, in Renaissance art—we often see explicit “New Eve” symbolism in lots of paintings of the Annunciation.

A dramatic example is The Annunciation by Giovanni di Paolo, c. 1445, in which the angel is seen approaching Mary in the foreground within a gazebo-style structure that is part of a sacred complex (church or temple). Mary is seated with her arms crossed over her chest in a posture of demurred humility.

Outside the structure, and behind the scene of the annunciation, an angel is escorting the naked and obviously dejected Adam and Eve out of the garden of Eden, under the direction of God, who looks down on them from a solar- type cloud.

By the 4th century, the doctrine of original sin was articulated (especially by Augustine). This is the belief that the original sin of disobedience committed by Adam and Eve in Genesis 3 is inherited by all humans from parents to their children– from one generation to another – through birth.

By the 8th century the theological problem arose—how could Jesus be born to a biological mother who was subject to original sin, and how could she be born without sin before her son’s act of Redemption?

In the 12th century John Duns Scotus provided the answer that stuck He decided “The Virgin was sanctified in the womb in anticipated application of the merits of her son.” This doctrine of Mary’s Immaculate Conception took root in Christian belief and became a predominant theme of Marian art though it was not made dogma until the 19th century.

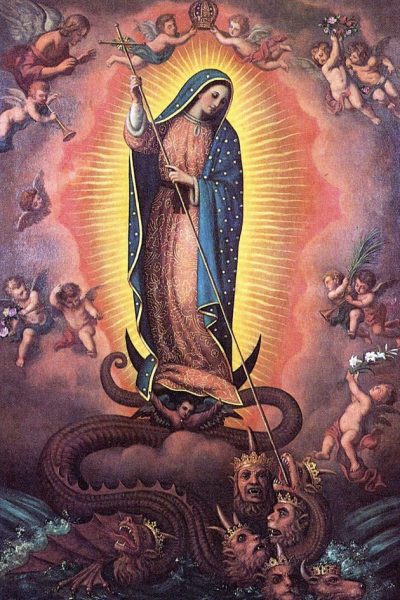

In essence, Mary’s immaculate conception—as the only fully human person not bound by the original sin committed by Adam and Eve, makes her triumphant over sin-death which is signified by serpent in the Garden of Eden.

This is depicted in historical and contemporary art with Mary standing on the head of the serpent. (Remember that the serpent’s punishment for his part in the fall was that his head would be crushed under a woman’s heel).

In the Madonna di Palefrenieri by Caravigio, 1602-3,

Mary supports the Christ child’s foot on head of serpent—symbolic of their roles as the New Adam and Eve.

Notice also how in contemporary church statues—Mary is almost always standing on the head of the serpent. The New Eve symbolism is still evident today.