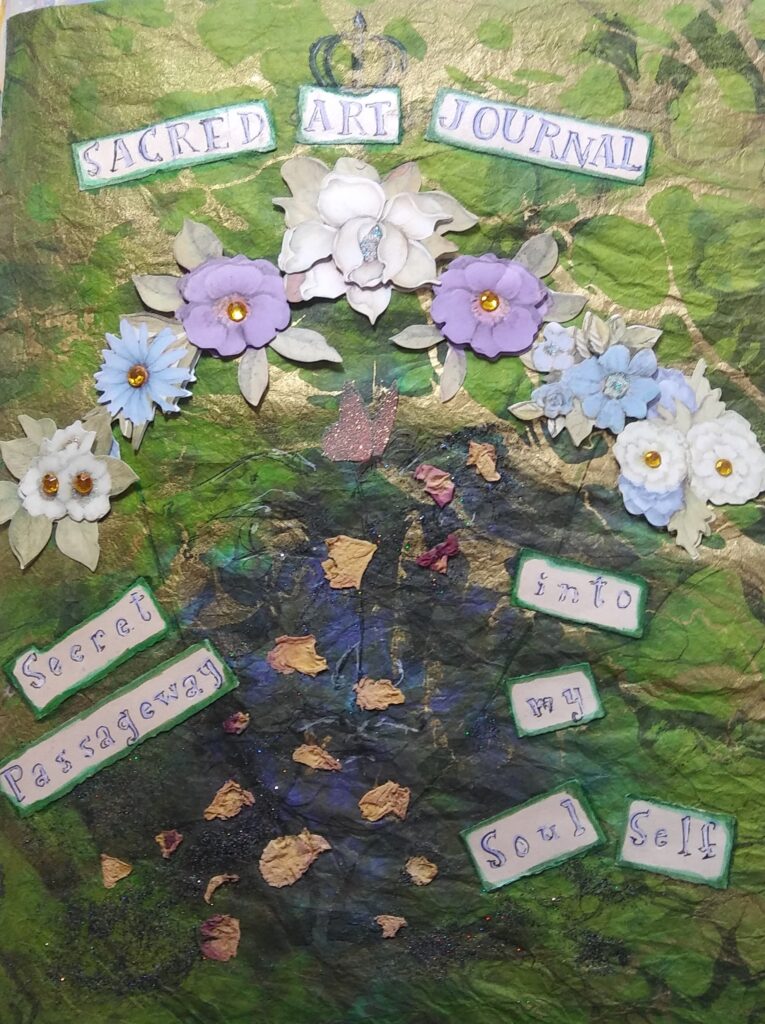

The Muses by Maurice Dennis 1893 (above)

Throughout history, prayer and sacred scripture

has been written or recited in poetic form. Poetry lends itself to spiritual

expression perhaps more readily than any other literary medium. In immersing

myself in within the world of women’s spiritual poetry, I have come to sense

that this genre of writing is decidedly different than other forms of

literature. Furthermore, it has a different “feel” than other types

of poetry,

Poetry expands the consciousness to embrace the

sacred. A poem is a mood, a complete little world unto itself, and each little

poem-world is open to the mysterious workings of the cosmos in that it may be

written, read, and interpreted in any number of wondrous ways. Its influence

cannot be estimated or restrained. Poetry is timeless and spaceless, so it is a

perfect mode of transcendence. It packs the full pith and punch of the metaphor

which allows it to create the same symbolic magic that is experienced within a

dream or lived throughout the telling and retelling of a cultural myth. For poets who consider themselves

spiritual, all poetry is spiritual, so what I am attempting to distinguish here

is the nuances of meaning that emerge from a typically female religious

consciousness as it has developed independently from the traditionally patriarchal

or predominately male religious-based consciousness of any particular culture.

This is still not to say I am trying to treat two separate spiritual-poetic

realities.

I started to collect, read, and appreciate women’s spiritual poetry as a specialized art and study, when I began to explore the vast world of my own sacred-art awareness and self expression. I was surprised to learn that many of the poems included in anthologies of women’s sacred poetry did not speak to divinity in any form I had ever encountered in the traditional sense. However, the way they elevated and celebrated the natural beauty of women’s bodies, homes, families, friends, work, and their natural environments; in short, the way they praised the trials and triumphs of the reality of life, felt far more sacred and transformative to me.

In the introduction to Wise Women, an anthology of women’s spiritual writing, editor Susan Cahill says that women’s spiritual writing is a “unitive” experience, which calls for a sense of transcendence from the confines of the individual self.[i] In her book Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, Jane Hirshfield also notes the unitive purpose in the “heart-mind” of traditional Japanese spiritual poetry in which she says the “concerns of the passionate heart flow seamlessly into the metaphysics of spirit.”[ii] The longing to unite the self with the larger Spirit as perceived in divinity, nature, community, or any combination of these pervades poetry that is generally characterized as spiritual.

In most cases, a unitive poetic melding of the individual self with the spiritual involves a tension between observed stark reality and the magic or mysterious potential of the sacred. Rita E. Guare sees this spiritual poetic tension of transcendence as a quest to unite the “interior landscape” of the self to a larger spiritual landscape. She states the purpose of her article “Educating in the Ways of the Spirit: Teaching and Leading Poetically, Prophetically, Powerfully” is to explore “the ways of spirit…through the rich language of poetry.” She hopes to induce educators and leaders to “visit their own interior landscape where the Spirit moves, stirs, and plays.”[i] Guare recognizes the poet’s vision involves a tension between the harsh realities of living in the real world and the “presence of things even as they may still remain hidden and holy.” She concludes that images created by the poet often “disturb and challenge us, evoking a kind of response that draws us beyond the narrow limits of self to seeing, reshaping, and ultimately, transcending the world in which we live.”[ii]

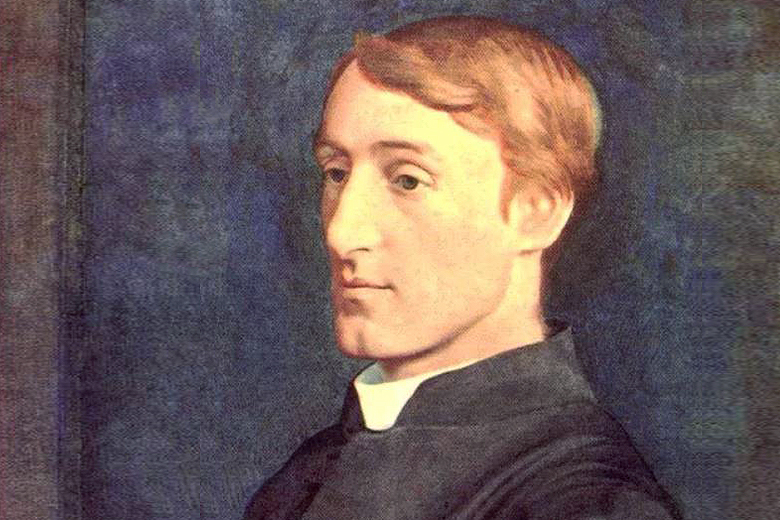

By way of discerning how women’s spiritual poetry differs from traditional patriarchal-based spiritual poetry, I will offer a spiritual-literary comparison between one traditional spiritual poem and one woman’s spiritual poem that I feel are generally representational of each genre. The first, “God’s Grandeur,” was written by Gerard Manley Hopkins in 1877, and the second, “Antiphon for Divine Wisdom,” was written 700 years earlier by Hildegard de Bingen.

GOD’S GRANDEUR by Gerard Manley Hopkins

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then and now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with the trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And through the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs—

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings

ANTIPHON FOR DIVINE WISDOM

Hildegard de Bingen

Sophia!

you of the whirling wings,

circling encompassing

energy of God:

you quicken the world in your clasp.

One wing soars in heaven

one wing sweeps the earth

and the third flies all around us,

Praise to Sophia!

Let all the earth praise her!

Hopkin’s and Hildegard’s spiritual poems both describe the author’s concept of how stark reality and the magical-mystical realms intersect to create a unitive sense of human transcendence into the Divine. The transcendental purpose of both poems is to unite the interior landscape of the self to a larger spiritual landscape as Guare noted of spiritual poetry in general. This is accomplished within these two particular poems by the creation of a cosmic scape within which the drama is played out between heaven and earth. Each expresses a consciousness of nature as sacred, and the Divine is metaphorically treated predominantly as a set of wings.

The difference in spiritual conceptualization is that Hildegard’s Sophia is obviously a mother-female divinity as evidenced by the way she “quickens” the world as the energy of God and the last line in which She is unequivocally addressed as “her.” Hopkin’s God bursts from the heavens with all the majesty and force of the ancient patriarchal sun-god, but in the last line he alludes to the Holy Ghost in metaphoric terms as a mother bird who “broods with warm breast” over the world.”

But a close look at how the unitive-transcendent experience is expressed in each of these poems illustrates what I believe is the fundamental difference between traditional spiritual poetry and women’s spiritual poetry. In “The Grandeur of God,” human transcendence into a unity with the divine is an encounter between two opposites. God is light and energy. “Man” is so embedded in the dirt and drudgery of the earth he can barely move. Even the actual encounter takes place beyond the duration of the poem and is conveyed as a hope that it might happen in the future with the “birth” of the light of morning pervading the brown-black reality of man.

In “Antiphon for Divine Wisdom,” Sophia infuses the human world with a unity that needs no “encounter,” because there was never a separation, and never a dichotomy of nature. The two were one from the moment she quickened the earth into creation. Divine energy is not just something that comes flashing down to earth from heaven if we are lucky—it pervades everything and always has. It is timeless and spaceless. The unitive experience is different—it is not so much an “encounter” within the poem, but the spiritual has always been embedded in the natural. The magical and mystical has always resided within stark reality. The spiritual landscape has always infused the interior landscape. Transcendence is when we discover this truth.

Wishing you Grace, Abundance and Joy,

Lori

Please join me for my monthly Women’s Sacred Poetry Circle Webinars. The sessions take place the third Tuesday of each month at 12:00 p.m. Eastern Time. The next webinar will explore the sacred poetry of Hildegard of Bingen further, with time for discussion and sharing of our own Sacred Poetry.

[1] Susan Cahill, ed., introduction to Wise Women: Over 2000 Years of Spiritual Writing by Women (New York, London: W. W. Norton and Company, 1996), xxiii.

[2] Jane Hirshfield, Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry (New York: Harper Perennial, 1997), 85.

[3] Rita E. Guare, “Educating in the Ways of the Spirit: Teaching and Leading Poetically, Prophetically, Powerfully,” Religious Education, vol. 96, no. 1 (Winter 2001), 65.

[41] Ibid., 67.

[5] Gerard Manley Hopkins, “God’s Grandeur,” in Literature: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, ed. X.J. Kennedy and Dana Gioia (New York: Harper Collins, 1995), 279.

[6] Hildegard de Bingen, “Antiphon for Divine Wisdom,” trans. Barbara Newman, in Women in Praise of the Sacred:43 Centuries of Spiritual Poetry by Women, ed. Jane Hirshfield (New York: Harper Perennial, 1994), 67.